A wobbly outcome: when voting systems attack

(For the purposes of this article, I’m only looking at constituencies in Great Britain. Sorry, Northern Ireland, but your politics are a rule unto themselves. Plus – we’re primarily concerned about who can win control of the UK-wide Government).

Since the election, we’ve heard a lot about how Labour’s support is “a mile wide and an inch deep.” We’ve also heard about how precarious is the Tory position; there is plenty of possibility for them to fall further. We’re all aware of how suddenly this change happened – from landslide in one direction to super-landslide in another. This just reinforces recent observation of just how sudden reverses can be (the Lib Dems in 2015, the SNP last month), how previously implausible collapses can suddenly seem not just plausible, but obvious. In hindsight, anyway.

We’ve all seen how turbulent the electorate has become, and that contributes to this. We’ve seen the proliferation of plausible (and semi-plausible) voting options, regardless of Duverger’s Law.

The thing that stood out to me, though, and partly as a consequence of all of these, was the proliferation of precariously-won constituencies. And I’m not just talking about marginality, although that’s part of it. To be honest, a precarious constituency is almost automatically pretty marginal. But what I’m looking at is the number of constituencies where the “post” was remarkably close to the starting line.

No winning post

One of the main characteristics of First Past the Post is that there’s no post. Neither does the time of passing any non-existent post have any bearing on anything. So “First,” “Past”, and “the Post,” are all misnomers in that phrase.

You can win with 26% of the vote (Russell Johnston in 1992 in Inverness). You can lose with more than 49% of the vote (Ronald E Simms in 1955 in Willesden East). It really depends on how many plausible contenders are around – but the fundamental principle is that winning with a very low share of the vote is extremely precarious. A lot of precarious wins leads to a chaotic position for future elections.

One major warning to the Lib Dems in 2015 that they were facing further potential losses was that five of their eight held seats that time around had vote shares in the thirties (two were even in the lower half of the thirties, in the sub-thirty-five range). All five of those were lost by 2019; two of those did not return even in 2024’s resurrection.

This precariousness is what I wanted to investigate. I’ve unilaterally defined that at winning with a share of 35% and below. FPTP is supposed to tend towards a tidy two-party hegemony, without widespread splintered vote shares. Because once you get into the lower thirties, your grip on the seat is very weak; you’re at around a third of the vote (or even lower). It’s not just that a majority of voters have voted for other candidates – pretty close to a super-majority will have done so. In some cases, beyond a super-majority.

It is, though, less precarious to win in the lower thirties on the way up (as you can secure your position after demonstrating that you can genuinely win and hopefully build a personal vote as well as put the squeeze on) than it is if you just hung onto a seat in the lower thirties on the way down.

Having defined this, let’s look at it: how common has it historically been it to win with a vote share in the lower thirties (or even lower, into the twenties)? And how prevalent was it in 2024 in comparison to other elections?

How often have we seen this before?

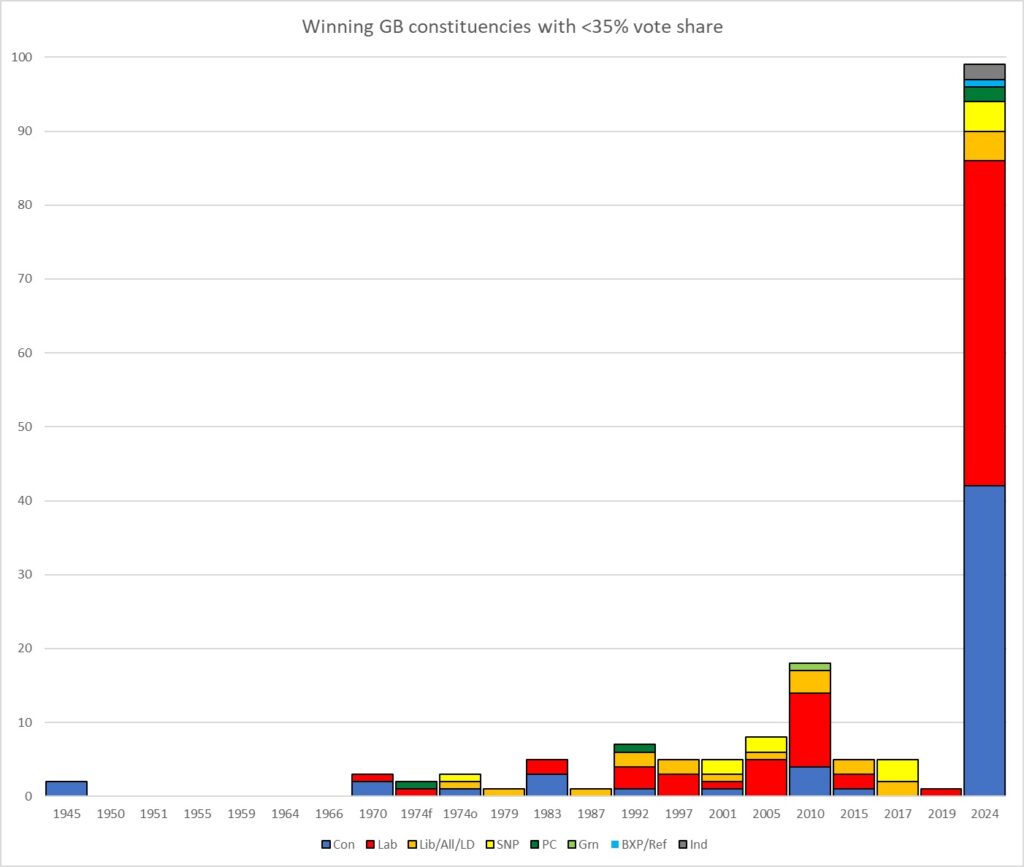

I went through each election since 1945 (it wasn’t worth going further back, as two-person seats and undernominations made comparisons difficult at best). And confirmed that winning with under 35% of the vote was almost unheard of in the post-war period prior to the Seventies: there were two freak three-way near-ties in 1945, and that’s it. This isn’t a surprise – it’s primarily due to the dominance of the Big Two in this era. If there are only two plausible candidates, you’re not going to see many wins without close to 50% of the vote. This is where “Duverger’s Law” holds an iron grip, and FPTP behaves itself.

The 1970s saw Plaid Cymru and the SNP become genuine electoral forces in their respective nations and things changed: we saw no fewer than nine instances of what I’m looking for in four elections: five such outcomes in Scotland and four in Wales. It was, though, still rare – we’re looking at between 1-3 per election and none in England.

England finally got into the game in 1983 as the Alliance became a genuine force, but these precarious wins were still very sparse (although 1992 saw the first ultra-precarious win with a score in the twenties anywhere in Great Britain, thanks Russell Johnston in Inverness). Even with the Lib Dems gaining traction during the Blair/Brown years, these sub-thirty-five wins were still rare: 5 in 1997, 5 in 2001, and a record 8 in 2005. Then 2010 saw the Cleggasm and whilst the Lib Dem hopes for a historic breakthrough turned into a damp soufflé, no fewer than 18 constituencies saw their winner in this category (with the first post-war sub-30 winner in England, in Norwich South).

Perhaps it would have gone further, but as the Lib Dem support collapsed post-Coalition, it all faded back down: only 5 in 2015, 5 in 2017, and only one in 2019 (Labour’s win in Sheffield Hallam).

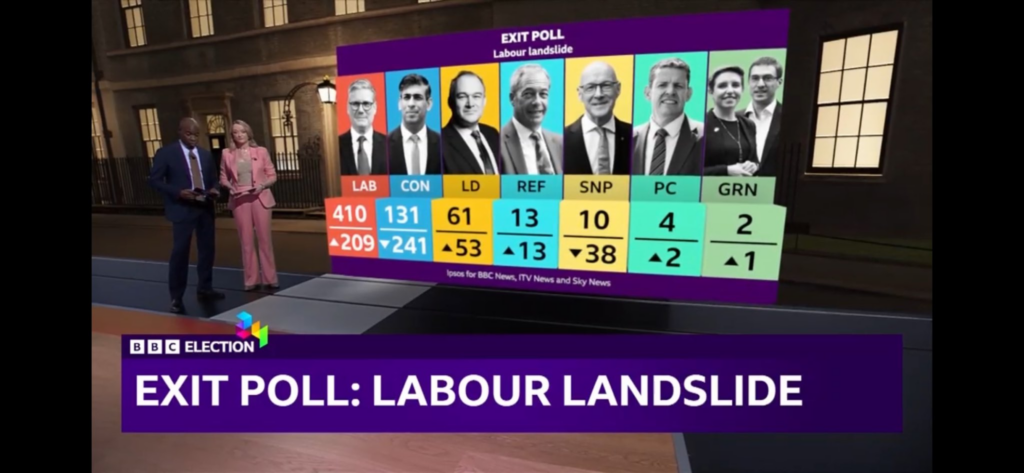

And then 2024 came in like a wrecking ball with 99 GB constituencies won with under 35% of the vote share, and seven won with scores in the twenties.

The graph shows this (I’ve separated out Scottish, Welsh, and English constituencies). Nearly one in six GB constituencies are now historically weakly held by their incumbent – when a precarious win like that was almost freakish before.

Implications

So, for Labour opponents – does this mean that Starmer’s support is built on sand? To a degree, yes: 44 of their 411 constituencies are in this precarious sub-35% boat (and 3 are sub-30%). More than a tenth of them. But… whilst we can expect Labour to lose overall support nationally, most (or all) of these were gained on the way up, and the local MP can be expected to work hard to secure their position and put the squeeze on by portraying it as a two-horse race. And, frankly, they can afford to lose 44 constituencies.

For Conservative opponents – does this mean that their current position is very shaky; that they could lose Big Two status? To a degree, yes: 42 of their 121 constituencies are in this sub-35% boat (and 2 are sub-30%). More than a fifth of them. But… whilst these dropped to this position on the way down (a big red flag), the Tories can at least hope to gain support nationally as Labour lose it. But their key risks are that it’s usually now clear who is their main challenger in each of these constituencies, and if Labour ends up losing support to the Lib Dems, Greens, and Reform rather than the Tories, it may well not help them at all. Unlike Labour’s position, losing the more precarious seats couldn’t be simply absorbed – it would be disastrous and likely slip them to third party status.

For those who dislike the Lib Dems, could we see their gains end up as ephemeral as morning dew? Possibly – but only 4 of their 72 seats are in this boat (only one in the sub-30% category). Nevertheless, it is true that what comes quickly can go just as rapidly, but when I started this analysis, I’d expected it to be worse for them here.

Of the smaller parties, the SNP and Plaid have the worst exposure – four of the SNP’s nine held seats are sub-35 and two of Plaid’s four. Only one of the five Reform seats are here, and no Green seats (the remaining two precarious ones are Independent-held; one of these being the last sub-30 seat).

So – what’s the upshot?

For me, if you tie the increasing tendency of the electorate towards volatility with the unparalleled number of precariously held seats (across the spectrum), it points to a strong chance that we could be in for interesting times indeed. Two crucial questions are:

• When unpopularity rises for Labour, to where does their support go?

• And how does that play out locally rather than nationally?

As it stands (or as it wobbles), small changes can lead to dramatic outcomes. Right now, FPTP is nearly broken. Our instincts – trained on the history of what we’ve seen – are questionable at best. Check your assumptions. In fact, check your assumptions at the door.

What people forget about FPTP is that it is only quasi-stable: whilst it usually looks pretty “well behaved,” this is only within certain conditions. It’s outside those conditions now, and counter-intuitively dramatic outcomes hove very much into view and are not priced in correctly. We tend to think either linearly or, at most, in a sort of bell-curve distribution of probabilities. This is much more jagged. Of course, this wobbling state could stabilise after all. Or it might not. Don’t assume.

Be very wary of those citing precedent – that such-and-such never happens, or would be unprecedented. They’re basing it all on those intuitions and history, and that’s an unstated assumption of its own.

Andy Cooke