The first cut is the lightest

UK finances are in a mess. Traditionally, the debate has been between the right, which favours a small-state but low-tax model like the US, and the left, which favours a Scandi-style high-tax but high level of services model. It feels like we are falling between 2 stools with high taxes and poor public services.

Some numbers from the ONS (September 2025):

- Public sector debt to GDP was 95.3%

- Public sector net financial liabilities were £2,564.8 billion and equivalent to an estimated 83.8% of GDP

- The UK Government borrowed just under £100 billion in the previous 6 months

- Public sector spending was 15 billion higher than in September 2023.

All chancellors have their own special rules to pretend they have the finances under control. Reeves has clearly lost control (although it is not entirely her fault)

I would argue the blame can be shared around:

- The late Blair Government increased public spending and put money on the credit card with things like PFI.

- The financial crash hit, and we spent a fortune bailing out the banks

- The coalition brought in austerity – but this consisted of slowing the rate of spending rather than a systemic overhaul

- The COVID pandemic led to a loss of work ethic and the end of spending restraint

- Reeves came in and started giving money to pet causes like the train drivers.

The UK used to have an AAA rating with the credit ratings agencies such as Moody’s. Since 2014, they have all downgraded us.

So what is to be done?

The chancellor has 3 options:

Borrow

Raise taxes

Cut spending

Pre-2010, borrowing was a realistic option as the UK’s debt was low. At this juncture, more borrowing isn’t realistic as the bond markets won’t wear it.

Reeves clearly intends to raise taxes, but that isn’t as straightforward as it looks.

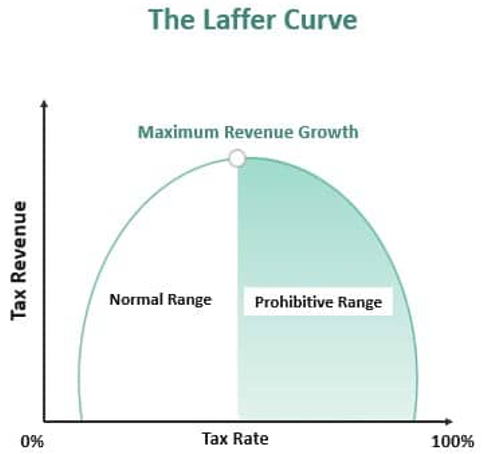

The Laffer Curve

Hopefully, most PB readers are familiar with the Laffer curve.

The UK tax burden is forecast by the OBR to reach 38.3% in 2027/28 a record high for the UK. It should be noted that this is only average across developed countries. France, Denmark and Italy to name three all have a tax burden between 40-45%. However, many of the European countries have a much more egalitarian culture than we do and better functioning public services. UK voters might be inclined to pay more if they could see a system that works.

The left would argue in favour of wealth taxes, however, the group in the UK who pay less than in Europe is actually middle earners. Reeves’ initial plan to raise income tax was the right course (although unpopular). The risk now is that small measures don’t raise enough and she has to come back again in March.

So then we come to cuts. Public sector spending jumped during the COVID pandemic and is now around 50% higher than pre-COVID (although there was that brief period of high inflation).

It feels like no-one is willing (or able) to get a grip of state spending in the UK.

3 examples of cuts

I’d like to share 3 examples of large cuts in state spending in other countries:

- New Zealand 1991 – The NZ Labour Party in the 1980s brought in a massive programme of economic reform that was dubbed “Rogernomics” after the then finance minister. This programme included almost Thatcherite elements, such as privatisations and the introduction of GST (VAT). By 1990, Labour were unpopular and lost to the National Party, which ran on a one-nation platform. National introduced massive cuts in their 1991 budget, dubbed the Mother of All Budgets or “Ruthanasia”. The cuts mainly fell on the welfare budget, reducing unemployment by $14 a week and sickness benefit by $27 a week. It also introduced charges for GP visits and other government services. National were re-elected in 1993 but with a reduced majority of 1.

- Canada 1995 – During the 1980s, Canada ran large deficits of around 5% and by the 1993 election, Canada was spending around a third of its budget on interest payments. The Canadian Liberals won power in 1993 and put forward a moderate budget in 1994 that didn’t solve the problem. In 1995, they then put forward a more radical programme that saw 19% cuts in programme expenditures, 73 agencies eliminated and 60% cuts to business subsidies. The Liberals were re-elected in 1997 with a reduced majority.

- Greece 2010-11 – Greece was a founder member of the Euro in 2001. It probably shouldn’t have been as the entry criteria were fudged. Being part of the Euro allowed Greece to borrow at low rates, while denying the ability to devalue its currency. When the financial crisis hit, markets lost confidence in the PIIGS to manage their debts and rates soared. This led to Greece requiring a bailout from the IMF and Eurozone. Greece, in turn, had to agree to a series of harsh austerity measures including cuts to public sector salaries, cuts to pensions, even cuts to health and education (some hospitals saw their budgets halve), and higher taxes as well. Youth employment reached 50%. PASOK (centre left) who were in power went from 44% of the vote in 2009 to 13% in 2012 (and 5% in 2015).

The lesson is that calling the IMF in, doesn’t end well for your party.

So how could we cut spending in the UK?

It feels like the Government is in a fiscal straightjacket. It is hard to increase taxes and borrowing. There are also long-term pressures on the Government to spend more on the NHS, Social Care and Defence.

The Government has to accept it can’t solve every problem.

For example, Labour has recently introduced a new football regulator. Now, no-one would deny that there have been issues with UK football, but is this really a priority when essential public services are struggling? For me, the problem with the Osborne austerity was that it cheesepared existing spending rather than looking at eliminating programmes completely.

Secondly, the Government is apparently conducting a zero-based spending review, and they need to be ruthless, even with minor spending. To update an old saw: look after the millions and the billions will look after themselves.

The reason I would argue a zero-based model is so important is that governments see a large turnover of ministers, all of whom have their pet projects. On top of that, we have 8 living former prime ministers who want to guard their legacies. We should also rethink the role of bloated and overly long Government inquiries, which all seem to lead to ever more layers of bureaucracy (for example, the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry has been going for 10 years with no end in sight).

The moral argument

Labour MPs voted down fairly modest reforms to disability benefits (it is worth mentioning the measures weren’t even really cuts as the total benefits bill would still have risen more slowly). The ringleaders wrote a letter including the following:

“The planned cuts of more than £7bn represent the biggest attack on the welfare state since George Osborne ushered in the years of austerity, and over three million of our poorest and most disadvantaged will be affected. Without a change in direction, the green paper will be impossible to support.”

Too many MPs seem to think they can govern without having to get their hands dirty. I would challenge these MPs: is it more important to be moral or to be seen to be moral?

In our social media world, the easy path is to oppose cuts and retain moral purity, however, failing to get a grip on our finances risks letting in a right-wing Government, which will bring in more severe cuts.

I would argue the moral path is for Labour to get a grip and introduce modest cuts now, while shielding the poorest and most vulnerable, to ward off a greater retrenchment down the line. This may also lead to a more virtuous circle, where the bond markets demand lower interest repayments as they see the Government is regaining control, allowing more flexibility on spending down the line.

Gareth of the Vale