The Challenge for… Reform UK

This is the third in a series looking at the challenges and opportunities for the 7 main Great Britain parties. Today we will look at the emergence of Reform UK.

Breadth vs depth

It is worth comparing Reform with the LDs, as the two sharply contrast. Reform got a slightly higher share of the vote in 2024, but the LDs got many more seats. To understand why, we need to look at the distribution of votes for each party.

| Vote share | Reform seats | Reform % of seats | Lib Dem seats | Lib Dem % of seats |

| 0% (Did not stand) | 41 | 6% | 20 | 3% |

| 1 to 5% | 39 | 6% | 266 | 41% |

| 6 to 10% | 118 | 18% | 189 | 29% |

| 11 to 20% | 320 | 49% | 79 | 12% |

| 21 to 30% | 124 | 19% | 19 | 3% |

| 31 to 40% | 6 | 1% | 24 | 4% |

| 40+% | 2 | 0% | 53 | 8% |

| Total | 650 | 100% | 650 | 100% |

The Reform vote follows a typical bell curve pattern with almost half of seats coming in the 11-20% range, which ties in with their overall vote share of 15%. Conversely, the LDs have a cluster of seats where they won a very high vote share, whilst at the other end of the scale there are a vast number of LD deserts (the poor candidate in Ynys Môn only got 1%).

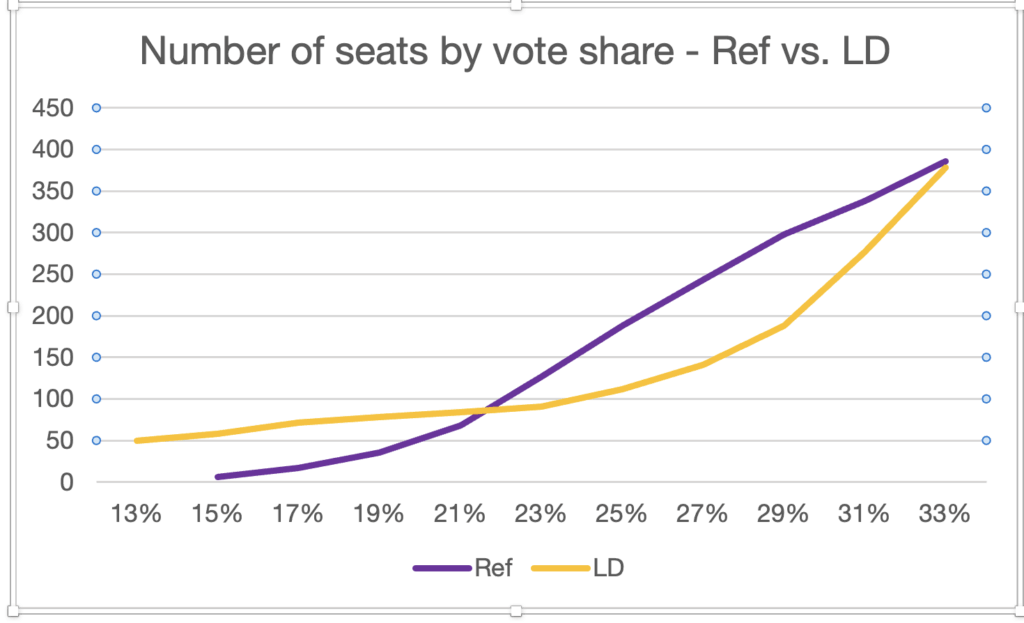

While this has hurt Reform in the short term, it potentially makes it much easier for Reform to gain a majority. Using the Electoral Calculus predictor, if we conduct an exercise where we take the 2024 result and add 2 percentage points each time to Reform or LD, while taking away 1 percentage point each from Con and Lab, we get the following:

Analysis conducted using Electoral Calculus software. NB: Electoral Calculus has the LDs winning fewer seats on a 13% share than they actually won in 2024.

So depending on how votes split for the other parties, Reform would win substantial numbers of seats from a mid-20s vote share, and could become the largest party with a vote share in the high-20s.

Insider vs Outsider parties

One thing I always remember is a Vox Pop from the 2015 election, where a voter said they were deciding whether to vote for the greens or UKIP. This challenges conventional political thinking, where we tend to group the parties into a right-wing block and a left-wing block. I would argue there is a second dimension, which is the difference between insider and outsider parties:

Insider parties – parties who work within the existing system

Outsider parties – parties who look to change the system.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the three main parties were all insiders. I would argue two main things changed that:

- The Financial Crisis – which led to austerity and a sharp drop in living standards. GDP per capita still hasn’t fully recovered, while the perpetrators largely got away scot-free.

- The expenses scandal – where MPs changed the rules to allow themselves to steal from the taxpayer.

Many people concluded that the system was set up to enrich and protect insiders at the expense of ordinary people.

From the 2010s onwards, we have seen a series of outsider parties, politicians and movements – the SNP, UKIP, Brexit, Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson*

*Boris was really an insider, but the resistance to Brexit allowed him to portray himself as an outsider.

The lesson from Brexit is winning an election is not enough. Reform need to prepare for a battle royale against the establishment/the blob, if they win (for example, they have zero members of the House of Lords).

Policy development

Last time around Reform’s manifesto resembled a wish list. Now they need build a detailed policy platform and look like a serious government in waiting. Labour’s Ming Vase strategy backfired on them and the same could easily happen to Reform.

If we go back to UKIP and the Brexit party, neither were political parties in the traditional sense. Instead, they were effectively pressure groups acting as backseat drivers to the Conservative Party.

While Farage is a charismatic front man for Reform, they also need a team of backroom people who can do the detail. It would help if there was a Reform aligned think tank.

Running local councils will give Reform the opportunity to build executive experience at local level. This will also be of benefit, as we would expect many of Reform’s future parliamentary candidates to come from their councillor pool.

Personnel issues

There was a joke about the old Liberal party that you could fit all their MPs in the back of a taxi and Reform are in the same position. Reform are trying to present themselves as an alternative government but they don’t have enough MPs to cover all the main portfolios.

There’s also the party demographics to consider. Nigel Farage is 61 and the next election will likely be his last chance to come PM. The current most likely successor Richard Tice is 60.

It’s vital that Reform gain more MPs. While the Runcorn by-election has helped, Reform will need more by-election gains and also Tory defectors if possible.

Reform must also retain their current MPs. Rupert Lowe is not the first to fall out with Nigel Farage.

The wavering pencil

You stand in the voting booth and have made up your mind. You are going to vote for Party X who will bring the change this country desperately needs. Then you hesitate. What if party X mess things up? Do they have enough experience? Maybe it’s safer to vote for Party Y after all.

What the above represents is late swing. Reform seem to be vulnerable to this. If we go back to the polling for 2024, Reform peaked about a week before the election, then dropped back. This late swing cost Reform the chance of double digit seats and also saved the Tories.

The challenge is how to be both the party of radical change and a safe choice. An effective example was Blair in 1997. Labour presented themselves as the party for change with the song “Things can only get better”, whilst setting out clear rules to reassure voters on the economy.

Tactical Voting

When we think of tactical voting, we tend to think of this as being left wing. Historically, there was a strong reason for this. Pre-2015, there were 3 major parties (Con, Lab, LD), 2 were on the left and one on the right. Without tactical voting, the left was at a structural disadvantage.

Now with 5 major parties (3 on the left and 2 on the right) in England, the right needs to start voting tactically as well.

It is a shame we can’t get the detailed breakdown of 2024 Conservative votes at the Runcorn by-election. There were rumours of some Conservatives voting Labour to keep out Reform, but my guess is more still went to Reform.

Another interesting question is whether having a more right wing party than the Conservatives somewhat rehabilitates them with the left. For example, say you are a Green supporter in Clacton. You could vote Green as your preferred party or Labour as the best placed left wing party but the best placed challenger to Reform is currently the Conservatives.

Scotland and Wales

Next year Reform should win seats in Holyrood and the Senedd for the first time.

In Scotland, Reform are unlikely to win any constituency seats but seem certain to win list seats. The first challenge is to beat the Conservatives. The SNP are looking unlikely to win a majority and have burnt their bridges with the Greens and so potentially we could see an SNP-Labour government. This could give Reform the chance to be the leading opposition party at Holyrood.

Where I think Reform are missing a trick is by not having a dedicated Scottish leader. With the Conservatives, Labour and the SNP all facing challenges, Reform could be the beneficiaries, but a lack of distinctive Scottishness may hinder them with soft nationalists.

In Wales, Reform have an outside chance of providing the next first minister, but what hinders then is their only possible coalition partner is the Conservatives.

Wales is moving to a system of list PR with 16 constituencies electing 6 MSs each. Reform can’t afford to cannibalise the Conservatives too much as they still need them the latter to win 1 MS per seat. Reform would then need to win 2 MSs per seat and perhaps 3 in their best seats.

I suspect that Reform will do well but fall a little short. It wouldn’t surprise me if we end up with a multi-way coalition of Labour/Plaid/LD/Green in some form. On the plus side, Reform would be the official opposition.

Targeting the middle class

Reform’s weakest area in England is a square roughly bounded by Bournemouth, Worcester, Cambridge, and Brighton. The reason for this is that this contains many of England’s most prosperous areas, including West London, Thames Valley and Surrey.

The challenge is also that this area has the greatest population growth. While Labour’s coalition traditionally focused on the working class, it also included parts of the urban middle class. With Reform unlikely to win in the inner cities or many parts of London, and also unlikely to feature in remain-y hotspots like Tunbridge Wells or Cheltenham, the key to winning a Reform majority is likely to lie in seats that have a mix of middle and working class voters and which were closer to the national average on Brexit e.g. Banbury and Basingstoke.

Next time – the Liberal Democrats

Gareth of the Vale