Not Another One?!

With all the demands for yet another inquiry, let’s look at the history of previous ones.

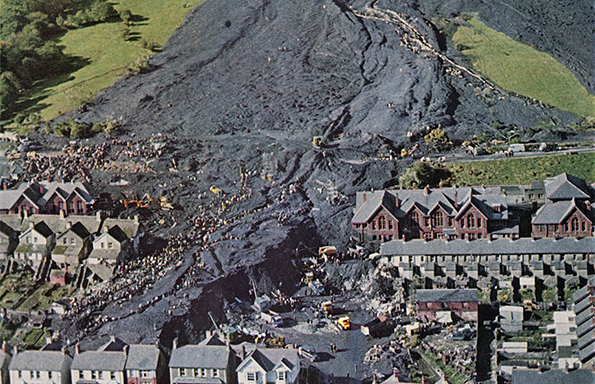

Five days after the Aberfan tragedy, a Tribunal was set up. It sat for 76 days – the longest inquiry for its type until then and, as its report tartly observed: “much of the time …. could have been saved if …. the National Coal Board had not stubbornly resisted every attempt to lay the blame where it so clearly must rest – at their door.”, behaviour described as “nothing short of audacious.” Only near the end did the NCB concede that, contrary to what it had repeatedly said, Tip 7’s instability could clearly have been foreseen, and was known by the NCB “even before the formal sittings of the inquiry had started.” Lord Robens, NCB Chair (former trade unionist and Labour politician) had denied responsibility throughout; his answers to the Inquiry were inconsistent and untrue. Like many politicians, he tried to spin his way out of responsibility, but his lies were caught by cross-examination by the families’ counsel. As a result, the NCB’s own Counsel asked the Tribunal to disregard his evidence.

The Report was published on 3 August 1967, less than a year later. That was one thing they really did do differently in the past.

Its findings were clear:

“… our strong and unanimous view is that the Aberfan disaster could and should have been prevented. … the Report which follows tells not of wickedness but of ignorance, ineptitude and a failure in communications. Ignorance on the part of those charged at all levels with the siting, control and daily management of tips; bungling ineptitude on the part of those who had the duty of supervising and directing them; and failure on the part of those having knowledge of the factors which affect tip safety to communicate that knowledge and to see that it was applied.”

As in many subsequent inquiries, the Report found that NCB officials and engineers had:

- Not bothered surveying the tips.

- Lied about not knowing about the underground streams making the tips unstable. The streams were known about and marked on OS maps.

- Ignored repeated warnings.

- Ignored earlier slides – in 1944 and 1963. Remarkably, the NCB tried to deny that the 1963 one had even happened.

- Not carried out any sort of investigation into the concerns and warnings raised, a failing which led the Report to say this:

“if there had been a proper investigation with a view to allaying the fears and resolving the doubts, the effect on the course of events must, in our opinion, have been dramatic and decisive.”

The Report was scathing about the evidence given by the main NCB witnesses. One of them W. V. Sheppard, the Coal Board’s Director of Production, was severely criticised for his ignorance of tip stability. The NCB and nine of its senior staff were named as responsible for the tragedy.

In 1963 Lord Robens had said in a speech to the National Union of Mineworkers:

“If we are going to make pits safer for men, we shall have to discipline the wrongdoer. I have no sympathy at all for those people – whether men, management or officials – who act in any way which endangers the lives and limbs of others.”

Despite the Report’s findings and Robens’ fine words, no action of any kind was taken against anyone responsible for the tragedy. Rather, Sheppard, the director whose ignorance had been particularly criticised, was promoted. Lord Robens stayed as Chair of the NCB until 1971 despite offering his resignation. It emerged many years later that it had been agreed in advance with the Minister that he would offer it but it would be refused. He had demanded (as a Privy Councillor) 10 days’ notice to see the Report before it was published and used that time to gain support for himself from the rest of the Board and the NUM. He even helped draft the letter the Minister sent refusing to accept his entirely bogus resignation letter. As in so many other scandals, the coal industry and Robens himself were seen as indispensable, especially by the then Labour government, which viewed coal nationalisation as one of the Attlee government’s shining achievements; he took full advantage of that to secure his personal position.

His behaviour and that of the relevant Labour Minister, Richard Marsh, were described by Labour MP, Leo Abse, in the subsequent Parliamentary debate, as a “disgraceful spectacle.” Many Welsh Labour MPs for mining areas were unable to criticise the NCB. Surprisingly, it was the Opposition’s spokesperson on Power who made some of the more pointed criticisms, asked questions (about the promotion of the ignorant director) which the government was unable to answer and pointed out that the Report said one of the remaining tips had “a very low factor of safety”. Their name? Margaret Thatcher.

What of Lord Robens? He had been criticised for not visiting Aberfan on the day of the tragedy because he was too busy being made Chancellor of Surrey University. The Chair of the Welsh NCB was at a conference in Japan and did not bother to cut short his visit either. Two years after the Report, in 1969, Robens was chosen by a Labour Minister, Barbara Castle, to chair a committee on workplace health and safety. It recommended self-regulation by employers. His choice as Chair was quite offensively insensitive.

Nonetheless, despite being Chair of an organisation responsible for one of the worst human tragedies this country has ever seen, he then became Chair of Vickers between 1971 – 1979, Johnson Mathey 1971 – 1983 and directors of various other companies as well as several other posts on the public and private sector gravy train. How very à la mode.

Has anything changed since then? No. Why?

– There is no institutional capacity, structure and willingness to join dots – not just within one organisation or sector – but across sectors and in government, regardless of the level of public pressure or whether the relevant politicians are interested.

– Politicians use public inquiries as a way of kicking embarrassing or politically sensitive issues into the long grass.

– As with Aberfan, the victims are treated with callous indifference, sometimes cruelly, are often lied to and compensation is minimised or delayed. Those responsible, especially the most senior, have to be very unlucky to suffer any consequences at all.

– The recommendations are often not implemented.

This was the conclusion of a House of Lords Report on Public Inquiries and how to make them more effective – “Public Inquiries: Enhancing Public Trust,” published on 16 September 2024. It makes the blindingly obvious point that there is little point to these inquiries (as well as being a colossal waste of time and money) if their recommendations are ignored and if, every time a disaster or scandal happens, a new inquiry has to “reinvent the wheel”.

A decade earlier, there was a previous House of Lords Select Committee Report on how public inquiries operated. It made 33 recommendations. 19 were accepted. Of these, zero, yes, zero (are you really surprised?) were implemented. So this latest Report has endorsed those earlier recommendations, is recommending them again and hopes that this time they will be implemented. What are the chances?

The Report also looks at implementation monitoring and reveals that it is informal and ad hoc. Paragraph 82 is worth quoting in full:

“We heard that if the recommendations from the inquiry into deaths at the Bristol Royal Infirmary had been comprehensively implemented, then the events investigated by the Mid-Staffordshire Hospitals Inquiry may have been less likely to have occurred,……. A lack of implementation is not just a problem for statutory inquiries. Witnesses told the Committee that if the recommendations from the inquest into the Lakanal House fire had been implemented, then the Grenfell Tower fire may have been less likely to have occurred. Emma Norris told the Committee that: “we see inquiry after inquiry make similar recommendations because the recommendations of former inquiries have not been implemented.” She gave the example of inquiries into healthcare where “almost every inquiry” makes “recommendations on the patient voice and blame culture. You see the same recommendations again and again.” This can come at a tragic cost to human lives and the suffering of the victims and survivors, and with a needless repetition of public inquiries.”

It went on:

“Witnesses told the present Committee that public inquiries often make recommendations which are common to other inquiries. Public policy failings rarely happen in isolation and there are often common themes which can only be identified by conducting meta-analyses of multiple inquiries. This function is currently missing from the governance structure for public inquiries and is not undertaken by the Inquiries Unit.”

Its recommendation is to establish a new joint Parliamentary Select Committee: the Public Inquiries Committee to monitor implementation and “compare and analyse multiple inquiry reports to identify common failures, which amount to more than the sum of individual public inquiry recommendations”.

This is all good stuff, even if it is depressing to read of the same fundamental issues arising here as elsewhere – the failure to learn from what has happened, the failure to join dots and spot patterns, the failure to implement any changes, the failure to share expertise, good practice, what not to do and so on.

What will happen to this Report? The government has said that it will respond within six months. March 2025 – mark it in your calendars. And then ……. ?

Cyclefree

This is an extract from Cyclefree’s forthcoming book on Scandals. Fond as she is of reading Inquiry Reports, there is little point adding to their pile unless they are used to do something useful – for the victims, above all, for those who will suffer in future if lessons are not learnt and for those in charge who need to be taught to take responsibility for their behaviour. One day, all or some of these may even happen.