Challenge for the SNP

This is the 5th in a series looking at the challenges and opportunities for the 7 main Great Britain parties. Today we will look at the Scottish National Party.

Feast or famine

Unlike Plaid Cymru, the SNP have a more consistent level of support across Scotland. In 2025, this ranged from 17% in Edinburgh South to 40% in Angus and Perthshire Glens. This means the SNP are often in a feast or famine situation. 30% of the vote in 2024 won them only 16% of the seats, while 37% in 2017 won them a majority of seats.

| Year | Westminster | Holyrood | ||

| Vote Share | No seats. | Regional Vote Share | No seats. | |

| 1997 | 22% | 8% | ||

| 1999 | 27% | 27% | ||

| 2001 | 20% | 7% | ||

| 2003 | 21% | 21% | ||

| 2005 | 18% | 10% | ||

| 2007 | 31% | 36% | ||

| 2010 | 20% | 10% | ||

| 2011 | 44% | 53% | ||

| 2015 | 50% | 95% | ||

| 2016 | 42% | 49% | ||

| 2017 | 37% | 59% | ||

| 2019 | 45% | 81% | ||

| 2021 | 40% | 50% | ||

| 2024 | 30% | 16% | ||

The currency

The SNP’s biggest challenge is which currency to have. There are essentially 3 options:

- Retain the pound in a currency union with the rest of the UK (RUK) – the currency would be shared and Scotland would have guaranteed seats on the Monetary Policy Committee. This is the best solution for an independent Scotland, but why would RUK agree? The lesson from the Euro is that Greece was able to borrow at German bond rates, but this then led to a crisis and resentment in both countries.

- The Montenegro option – Scotland could unilaterally adopt the Pound (or the Euro). The challenge with this is that Scotland would then have no say on interest rates. Also in a crisis, it would not be able to print its way out of trouble or use quantitative easing.

- Own currency – Scotland could create a brand new currency, e.g. the Groat. The problem is that assuming Scotland takes a pro rata share of the UK’s debts, it is likely that the bond markets would demand a significantly higher interest rate for an independent Scotland.

Barnett and the oil hole

The Barnett formula was devised in 1978 by Labour minister Joel Barnett. It was designed as a short-term measure to allocate spending between the 4 home nations and, like many “short-term” measure, it is still with us.

It should be noted that Barnett is now incredibly unfair as Scotland gets a higher per capita spend than Wales, despite Wales being poorer. Westminster has no incentive to fix this though as Barnett delivers a union dividend. The difference works out to be about £2,000 per head compared to England, which allows Scotland to offer free tuition fees as an example. The question then becomes to Scottish Nationalists: what would an independent Scotland cut first?

At the last referendum, the SNP’s answer was oil.

While the SNP have been around since the 1930s, their support really started to take off in the 1970s and 1980s with the development of North Sea oil. The economic argument was simple: an independent Scotland will get all of the oil and become richer.

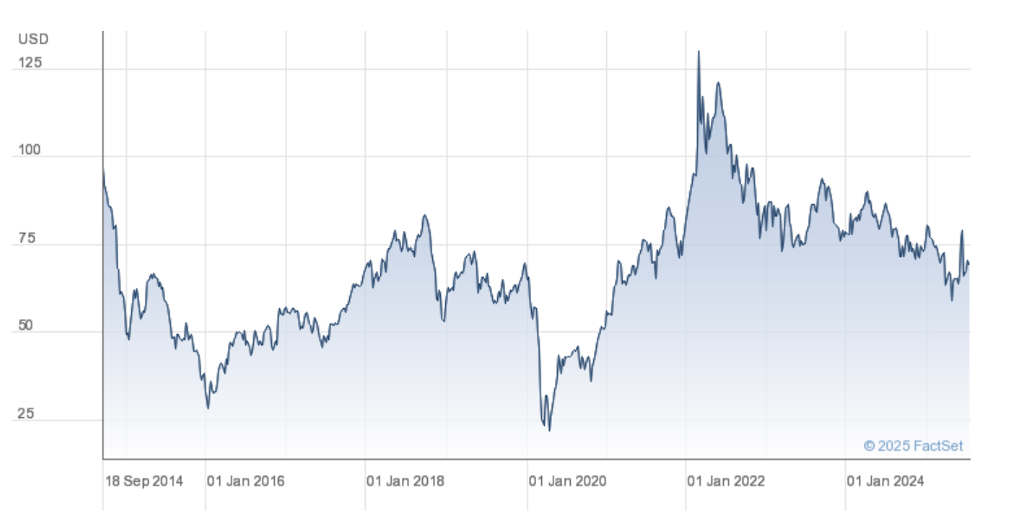

Perhaps one of the ironies of the 2014 referendum is that the price of oil declined sharply immediately afterwards, not to reach the same level until the 2020s.

Price of Brent Crude from 18th September 2014 to present day – source HL.com

One of the things that I find slightly inexplicable is that Nicola Sturgeon’s government was against new drilling. North Sea oil has declined from 884 million barrels in 2010 to 552 million in 2022 and is predicted to fall to 251 million barrels in 2030 (source BBC).

If North Sea Oil was going to pay for independence, what can the SNP replace it with?

The 3 bar gate

Nicola Sturgeon’s referendum court case has proved disastrous for nationalists as the Supreme Court ruled that the Scottish Government cannot unilaterally hold a referendum. This means that there are 3 hurdles to Scottish Independence:

- Independence supporting parties need a majority in Holyrood

- They need Westminster to grant permission to hold a referendum

- They need to win the referendum

By contrast, it was easier for the Brexiteers as they didn’t need permission from Brussels.

The challenge here is that Westminster can always find a reason to say not now (a Prime minister who lost Scotland would have to resign) so the SNP need to hope for a hung parliament situation where Labour can’t rely on the LDs alone e.g. Labour 240 seats, LD 70 seats, SNP 50 seats.

Even then, I suspect the deal would require the SNP to be good faith coalition partners before a referendum was held, e.g. a referendum taking place in year 4 of a coalition. That risks the SNP’s appeal being tarnished by being in power in Westminster.

Alternatives to a referendum

The SNP have at various times floated alternatives to a referendum. One of these is to treat the next Holyrood (or Westminster) election as a de facto referendum. There are a couple of problems here:

- While the SNP may win the most seats, the unionist parties may have a majority of votes (especially if Reform can nibble into the soft nationalist vote.

- Even if the nationalist parties do get a majority, the unionists won’t accept it.

That then leads logically to UDI (unilateral Declaration of Independence) as a next step. The problem is that the SNP could make a grand announcement and everyone ignores them. Then what? An independent Scotland would need international recognition to be successful and it won’t be forthcoming with UDI. Perhaps Russia might as a troll.

The double-edged sword of Brexit

On the face of it, Brexit ought to be to the SNP’s advantage. However, I would argue that it has actually made Scottish independence harder. Alex Salmond’s plan in 2014 was to leave both the UK and the EU. The SNP used to talk about an “arc of prosperity” including Iceland and Norway (before Iceland got badly hit in the financial crisis).

Under Sturgeon, the SNP moved to a more pro EU position. Brexit ought to have been a boost to independence as Scotland was taken out of the EU despite voting remain. However, it actually makes things more difficult. If the UK had voted to remain then Scotland would have had a safety net by being able to stay in the EU as an independent country.

However, now the UK has left, an independent Scotland would have to reapply. In addition, the UK had various opt outs such as on the Euro and Schengen, which Scotland would be unlikely to get again. And of course, every year that passes, EU and UK laws drift further apart.

There is also the problem of every current EU country having a veto. The Spanish socialists have no issue with an independent Scotland joining the EU, but a future PP and Vox government might well object (the SNPs support for Catalan independence is unlikely to play well here)

Coalition partners

The SNP are set to be the largest party in Holyrood after the next election in 2026. In particular, the rise of Reform splits the unionist vote even further and makes it likely that the SNP will win the majority of Holyrood constituency seats.

The question is who to partner with. They have fallen out with the Scottish Greens and it is questionable whether they can and should do a new deal with them.

There has been talk of crossing the divide and making a coalition with Labour. That might suit both parties but would likely leave Reform as the main opposition. It could also lead to cries of betrayal from the most vocal nationalists.

With the death of Alex Salmond, Alba’s chance to breakthrough may have faded, but there are other challenger independence parties looking for a chance to cry treason

The leadership

The SNP were blessed with two political titans in Salmond and Sturgeon, but are now finding it tougher going. While John Swinney has steadied the ship after Humza Yusuf’s disastrous tenure, he very much looks like a short term option.

Tension has arisen within the SNP because the independence question is the one thing that unites the party. Under Salmond, the party was economically more right wing and small c conservative. Under Sturgeon, it was economically left wing and progressive. The tension is between appealing to Middle Scotland and satisfying an increasingly left-wing activist base.

Overall, the SNP may win the next Holyrood elections and remain in government via some sort of coalition, but independence seems a long way away. If their one unifying factor is off the table, it may prove increasingly hard to reconcile the different wings of the party.

Next time – the Green Parties

Gareth of the Vale