Tories forever?

There used to be such a thing in politics as the pendulum. Rather like its physical counterpart, it appears to have gone out of fashion. In fact, there were two pendulums operating simultaneously, one between general elections and one across them.

The intra-election pendulum would traditionally swing away from the government after it was elected, as it created a lot of disruption implementing its reforms and, probably, front-loaded other unpopular decisions it felt it had to take, while it had the chance. Opinion would then swing back to the government later on as it stopped doing those things and – it would hope – the benefits of those earlier measures came to be felt. The government might also benefit as the election neared from the public taking a closer look at the opposition.

The longer-scale pendulum had a similar logic. Oppositions win elections because they’re good at campaigning, have something to say that the public buys into and are facing a government which is one or more of tired, failed and divided. As time goes on though, that freshness goes, campaigners are replaced by administrators (or else campaigners prove themselves poor administrators), past successes are discounted the governing party – unlike the opposition – finds it hard to refresh itself. Additionally, unhealthy habits of arrogance and entitlement creep in.

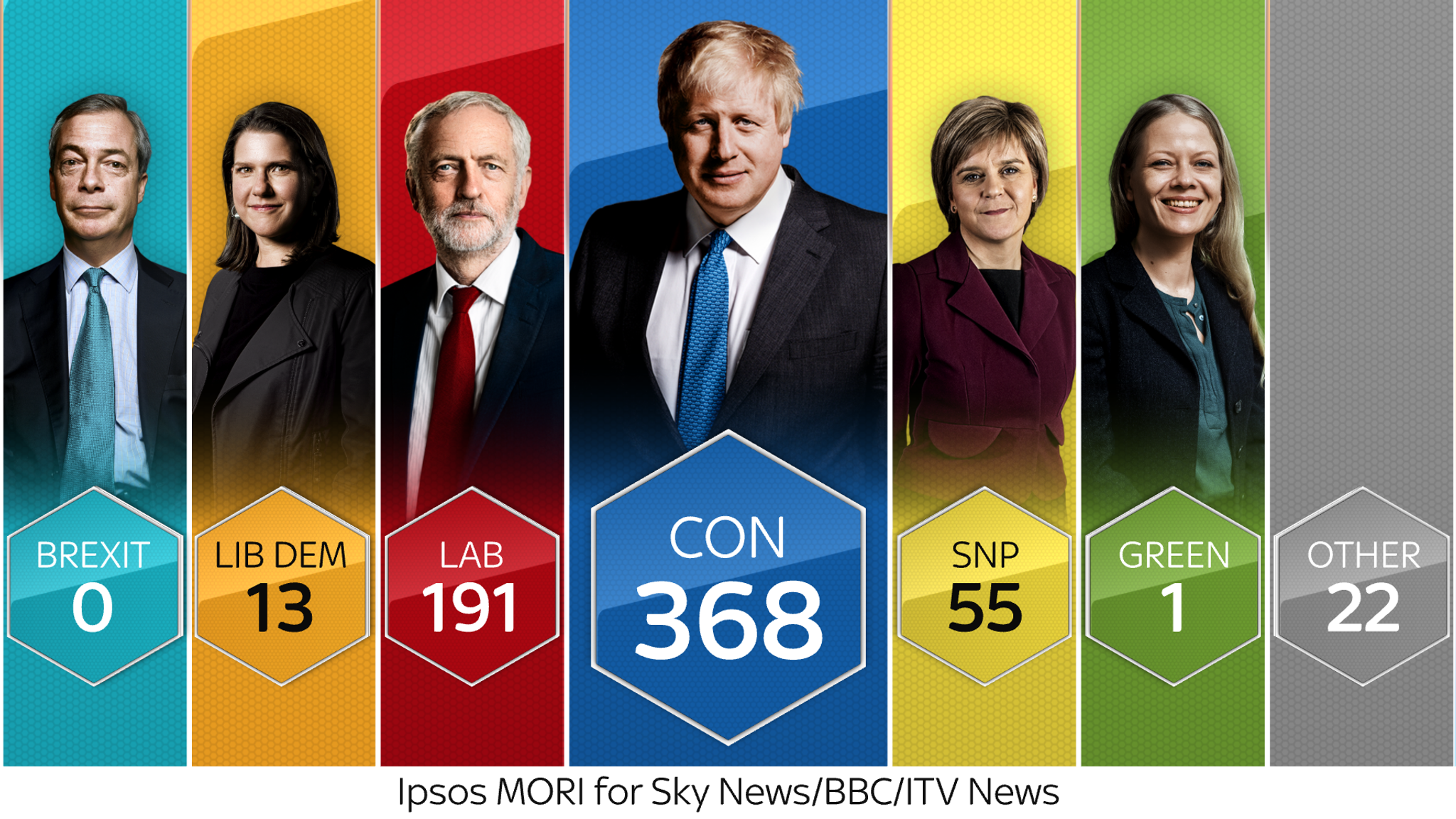

And yet here we are, sixteen months after the fourth successive Tory general election win with the Conservatives chalking up leads of at least 7% in each of the last fourteen polls, stretching back almost a month, and hitting 14% with YouGov, published yesterday. All the normal rules say that Labour ought to be way ahead and heading towards victory but the normal rules no longer apply – hence the question whether Britain (or England at least) is stuck with Tories forever?

One simple (and accurate) response would be to say that the normal rules don’t apply because these are not normal times. Let’s look again when a global crisis is no longer underway, when parliament is fully sitting again and when the economy, crime, health service, government standards and so on are the focus of attention. Because for all the errors made in the fight against Covid in 2020, the government has got a lot right in 2021 and is receiving plaudits for that – and that’s a temporary effect which will fade.

We only need to look back to the start of the year – before the vaccine roll-out and when daily Covid cases were at their worst (after a mismanaged Christmas easing) – and polls were more or less level. And yet that’s the point. ‘Level’ is not where Labour should be if the pendulums were working as normal.

A year after the 1992 general election, Labour was regularly scoring leads in the mid-teens. A year after the 2005 general election, the Tories led by mid- to high-single-figures. Both would go on to win although it was not a done deal at this point. But crucially, both parties had broadly accepted the need to adopt themselves to the electorate rather than hoping to reform the electorate to them. Labour now is very far from that point; the myth of 2017 is still too powerful.

Hence all the criticism Starmer is now getting from vocal leftist activists who may or may not be representative of the party overall but who can certainly make a nuisance. And some of their criticism is merited. Unlike Blair or Cameron (or Smith, if we’re comparing to 1993), it’s still much clearer where Labour is coming from than where it’s going to. There’s not any vision of a new Britain, never mind policies to put that vision into place. Nor is there any lasting critical narrative of the government – two or three key themes to tie 90% of the attacks into and so set those stories in the public mind.

But there may be more to it that political ability, historic legacy and happenstance of events. In one sense, members of the electorate define themselves less by party than ever before; politics has become more transactional. In another though, number of voters switching directly between Lab and Con (the traditional swing voters) remains low, as it has for years – and where it is happening, it tends to be a bringing into alignment of the social cultural values of the voter with the party. In other words, these are not true swing voters, backing one or other main party for transactional reasons or on grounds of competence.

That’s borne out by the YouGov survey (which it should be noted is well out of line with other recent polling and may be an outlier but is interesting for that very fact). According to that, only 6% of 2019GE Lab voters would now back the Tories, with 3% going the other way. Against that though, the Tories have the backing of some 69% of Leave voters, whereas Labour can only count on 44% of Remainers (you might argue that these are irrelevant labels now, which in terms of Brexit they are, but Brexit stance is itself a proxy rather than an ideological starting point).

For Labour to win, it needs to collect Remainers back into its corner or heal the divides that have so reduced the cross-values switching, which it should be able to do – if it wants to. And there lies the problem: does it want to? Does it want it enough? Can it stop the infighting? Can it find a purpose it can unite behind and sell to the country? None of these is anything like a sure ‘yes’ yet. Indeed, if Labour does lose, it’s entirely possible that it could reject the Starmer leadership as an internal Right Opposition that deviated from the true path that so nearly won in 2017 – and in so doing, jeopardize the election after that.

I don’t believe that the Tories really can win forever but another general election victory in 2023/4 is very realistic. At the moment, the Tories are 7/4 with Ladbrokes to win another majority, which strikes me as value – particularly as the boundary changes should improve their position further. And this is without considering the possibility of Scotland seceding from the Union.

No party since before the Great Reform Act has won five elections on the trot but if it’s right that identity and values politics are now so important, then to a large extent the post-Covid era won’t and can’t be a return to a pre-2010 ‘normal’. That world has gone.