MRP ELECTION MODELLING: HOW USEFUL IS IT OUTSIDE OF AN ELECTION PERIOD?

When YouGov published their multilevel regression and post-stratification (MRP) election model during the 2017 General Election campaign, it’s fair to say that it was met with a great deal of scepticism (though not from Alastair Meeks). Sure, expectations about the size of the Conservative majority had been scaled back, but a hung-parliament? Labour gain Canterbury? No chance…

In the end the Tories did a little bit better than the model predicted and Theresa May clung on to power. But the world had changed and come 2019, we waited for the publication of the YouGov MRP with almost as much anticipation as the exit poll.

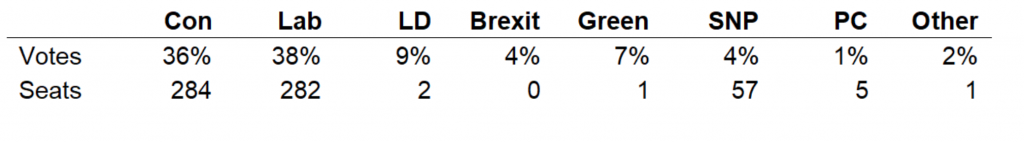

There were a couple of new entries to the MRP scene in 2019. One of which, Focal Data, recently published the results of their model for the next election (which I’ll assume will be in 2024). Using data collected during December 2020, they project the following vote shares and seat totals (excludes Northern Ireland):

The main headline was that the Conservatives were losing support in the Red Wall, while the Lib Dems falling to two seats also caught the eye. I thought it would be interesting to take a closer look at this latest model in more detail. The data and additional charts can be found in this spreadsheet.

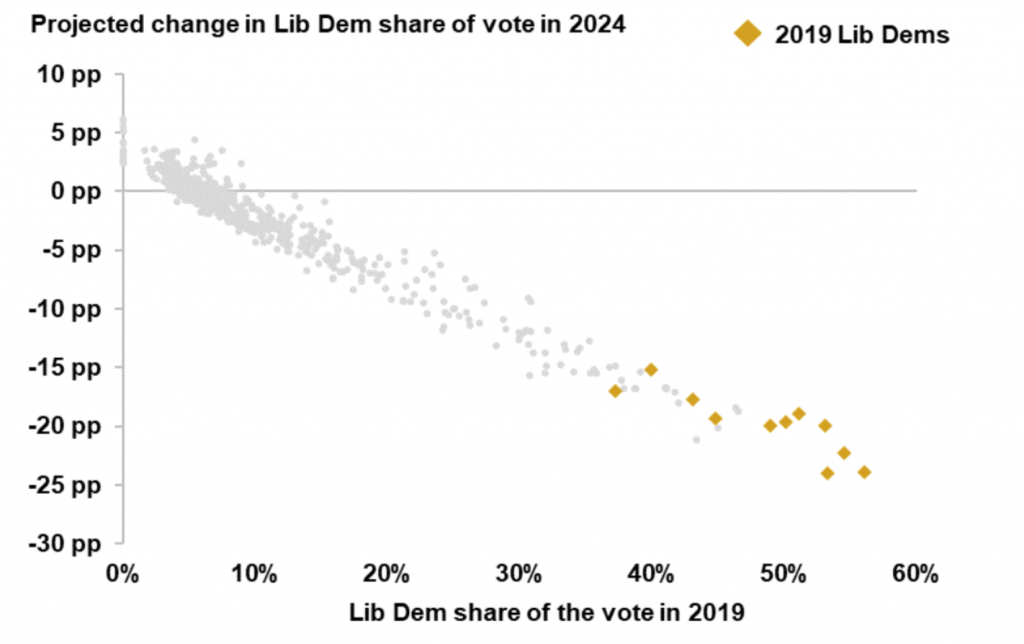

1) Treat the Lib Dem figure of 2 seats with caution

The chart below shows the projected change in the Lib Dem share of the vote against their share of the vote in 2019. The MRP suggests that the Lib Dems will suffer larger percentage point decreases in seats that they won more of the vote in 2019. Moreover, the 11 seats won by the Lib Dems in 2019 are projected to fit the same trend as the other 621 seats.

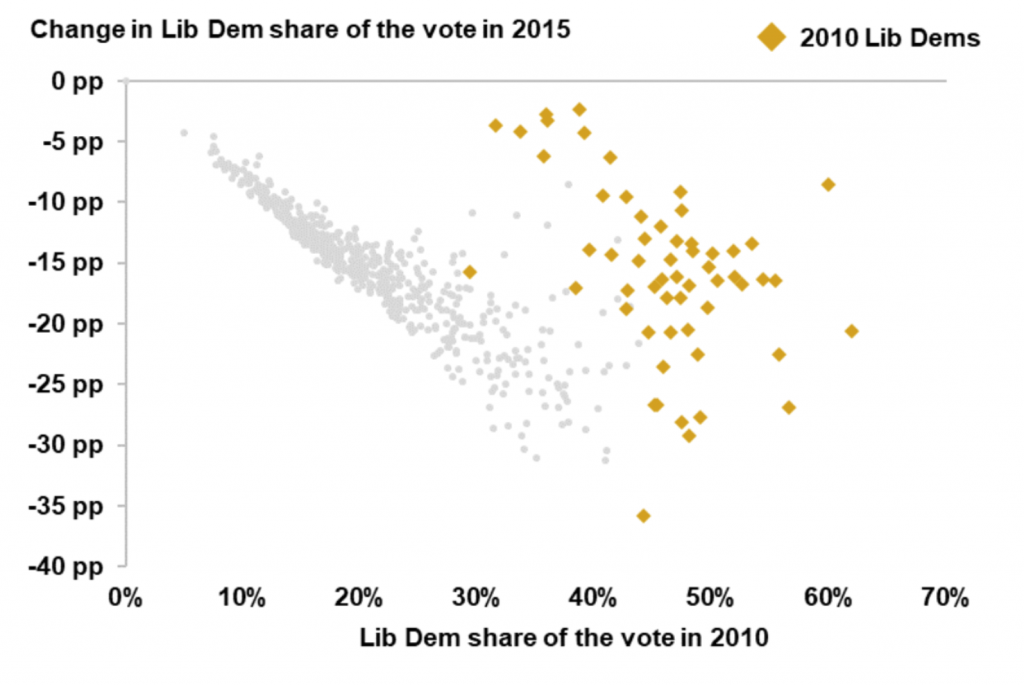

Contrast the MRP chart with the one below that shows how the Lib Dems performed in the 2015 election. Unsurprisingly the Lib Dems lost more votes in seats that they had more votes to lose, though the strength of the trend weakened as the 2010 share of the vote increased. Unlike the MRP projection for 2024, the Lib Dems did better in the seats that they were defending.

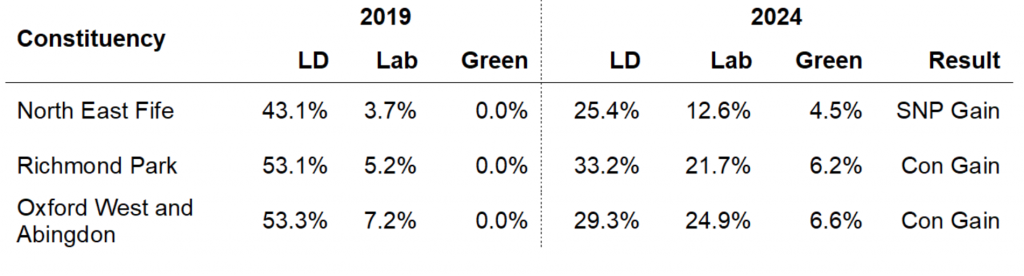

It’s worth noting that Focal Data have the Lib Dems losing seats to the SNP and the Tories thanks mostly to the Lib Dems losing votes to Labour and the Greens (who did not contest eight of the 11 seats won by the Lib Dems in 2019). Here are some examples:

Anything is possible, of course, but it feels as though the model isn’t detecting any tactical voting in such seats or for that matter in seats like Wimbledon (Tory hold in 2024 according to Focal Data) where the Lib Dems recorded a clear second place in 2019.

2) There’s no sign of a sophomore surge for the Tories

I recently re-watched the 2002 BBC fictional drama The Project, which followed the lives of four young Labour supporters during the rise of New Labour. Maggie Dunn (played by Naomie Harris) wins the fictional seat of Wroker from the Conservatives at the 1997 General Election. On her first day in Parliament she is told by a Tory MP: “That seat’s only on loan; we’ll have it back at the next election.”

In reality, the Conservatives only regained five of the 144 seats that they lost to Labour in 1997. Indeed, Labour increased their share of the vote by an average of 1.8 pp in the 50 seats most vulnerable to the Tories. Nationally Labour’s vote fell by 2.5 pp. This may have been partly due to overambitious targeting by the Conservatives. However, it is also likely to be an example of the sophomore surge, also known as the first-time incumbency bonus.

Essentially incumbents tend to receive a bonus in all elections, but it is most noticeable when an MP defends a seat for the first time having defeated an incumbent at the previous election. For example, Stephen Twigg defeated the incumbent Michael Portillo in 1997 with 44.2% of the vote. When defending the seat for the first time in 2001, he achieved 51.8%.

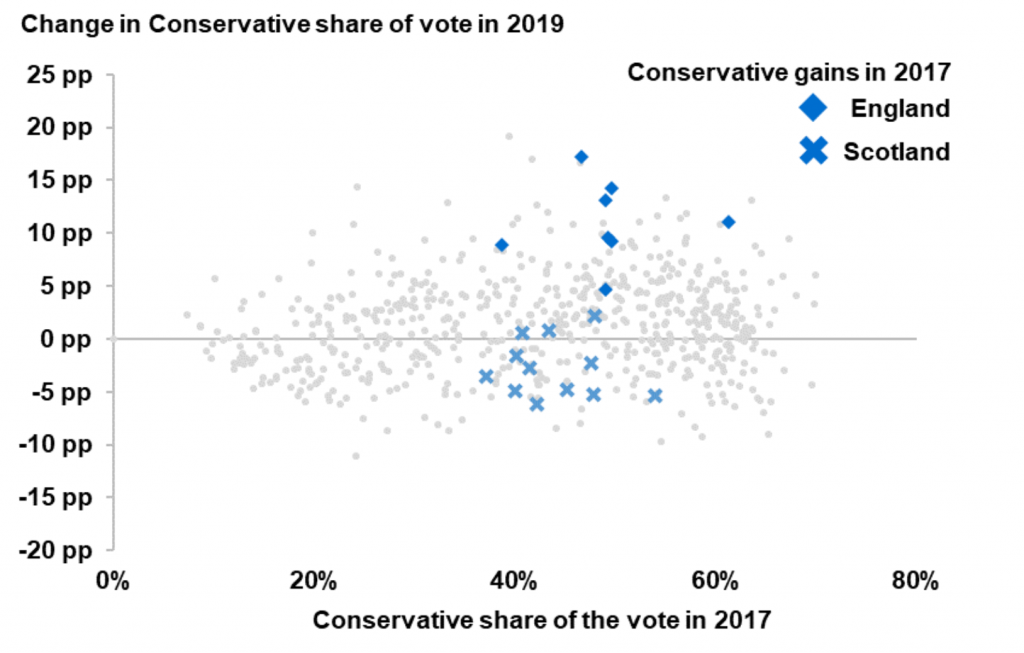

Similarly, in 2019 the Conservatives recorded substantial increases in vote share in the eight English seats that they gained in 2017. Whilst things didn’t go nearly so well for them in Scotland, the Tories still performed marginally better in the 12 seats gained in 2017 compared with the other 47 Scottish seats.

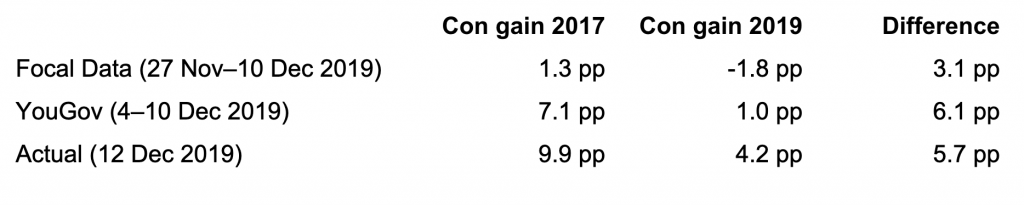

The table below shows the projected and actual increase in the Conservative share of the vote at the 2019 election for seats gained in 2017 and 2019. Both Focal Data and YouGov projected a better performance by the Tories in the seats they gained in 2017 compared with those that they would go on to gain in 2019.

The point is that even though the MRPs understated the Tory gains in 2019 (by quite some margin in the case of Focal Data), they correctly predicted better performance in the seats gained at the previous election.

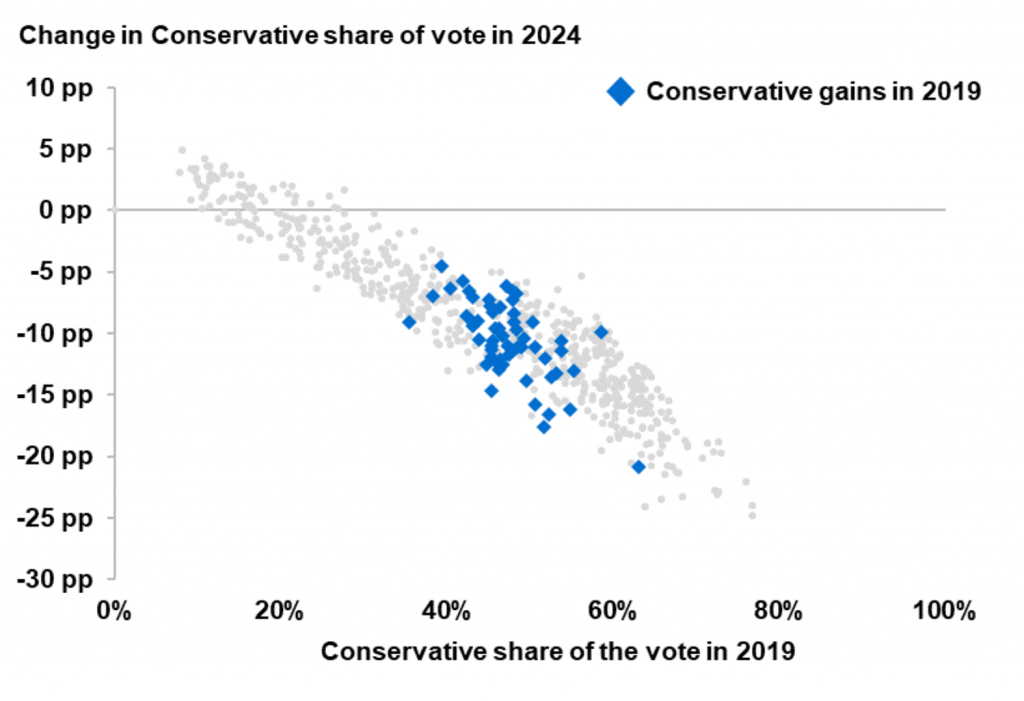

The chart below shows that the 57 seats gained by the Tories in 2019 are in line with the rest of the seats in Britain. Past performance is no guarantee of future results, but it’s interesting to note that the Focal Data MRP for 2024 does not appear to identify a sophomore surge for the 2019 gains. Only time will tell if this is because it won’t happen in 2024 or because the MRP isn’t currently detecting it. But I would expect an MRP to spot it if it is going to happen.

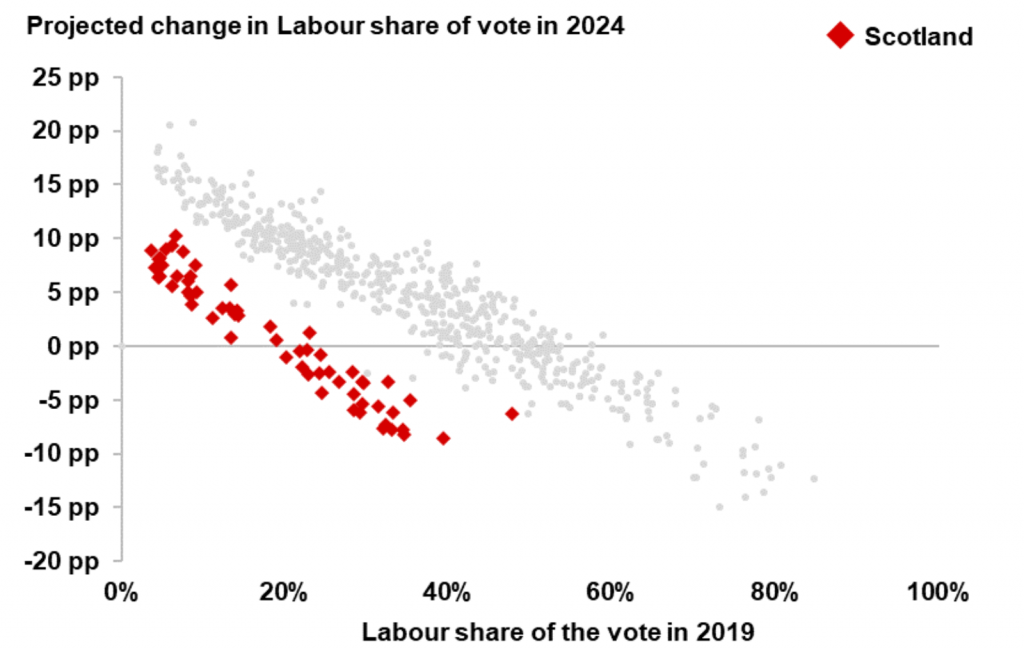

3) Labour are performing less well in Scotland compared with England and Wales

Unsurprisingly the Focal Data MRP for 2024 suggests that Labour aren’t doing so well in Scotland. The chart below shows that the projected change in the Labour vote in Scotland is worse for a given share of the vote in 2019 compared with a similar seat in England or Wales. The one exception is Edinburgh South – Labour’s only Scottish seat – which is closer to the England and Wales trend.

Nevertheless, in England, Scotland and Wales the MRP suggests that Labour are doing better where they were weaker in 2019. It’s a similar story with the Brexit Party (now Reform UK) and the Greens, though both didn’t stand in a substantial number of seats in 2019.

In fact, it’s only the SNP for which this trend is not nearly so obvious. On the subject of the SNP, the projected increase in their vote share for their nine gains indicated by the MRP is 0.1 pp. That is to say that these gains would be as a result of swings from the Conservatives and the Lib Dems to Labour.

Conclusion

I’m happy to admit that I was sceptical about the YouGov MRP in 2017, so I’m very much aware that I might be making the same mistake again. However, my suspicion is that Focal Data have revealed how the electorate behave between elections. There isn’t an election tomorrow and people are not thinking about things like tactical voting.

That’s not to say that I think such modelling is not worthwhile outside of an election period. But I suspect that as with opinion polling, the value will be in assessing changes over time.

Tom Leveson Gower

This is Tom Leveson Gower’s debut piece for PB, he is a longstanding poster, and posts as TLG86