Theresa Maybe? Definitely not

It’s only eight weeks since The Economist’s cover story but the mood has changed decisively

At the turn of the year Theresa May was besieged by many similar opinion pieces, several of them prompted by Sir Ivan Rogers’ resignation on 3rd January. Indecisiveness was the central charge, specifically over Brexit but also with regard to the operation of her Downing Street office and some rushed and/or reversed policy announcements. Her predecessor’s alleged nickname for her – “Submarine” – was used against her in articles that specifically did call for a running commentary.

And yet barely eight weeks later she dominates the scene to such an extent that three-figure majorities seem to be the mere beginning of her possibilities. Bruce Anderson writes, without hyperbole, that the “Tories have an historic opportunity to dominate British politics.”

These eight weeks have been busy – the Supreme Court verdict, the Trump trip, the progress of the Brexit Bill and the by-elections – but a flannelly White Paper aside, Mrs May hasn’t had to reveal much more of her thinking. The FT’s Janan Ganesh sums this all up: “Theresa May runs an imperious government and still no one knows if it is any good.” She may well be a submarine, but if so she’s clearly an Astute one.

She has, of course, been lucky in her opponent, and for once I’m not talking about Corbyn. Gina Miller’s misguided case showed why politics is usually best left to the professionals. Though I do not question her right to have brought the claim, and I thought the Supreme Court’s verdict was unsurprising and sound, she won a victory that King Pyrrhus himself might have thought a touch costly. This process: (a) bought Mrs May’s government some time; (b) united the bulk of her party behind her; (c) made [some of] the Remainers look unreasonable; and most of all (d) helped to persuade the public to accept a harder Brexit, at least as our stated opening negotiating position.

The signs were there earlier

The Economist had a point that some of Downing Street’s early policy announcements were a bit muddled. I think this is chiefly attributable to the surprisingly swift nature of her elevation to the top job [and the associated promotion of her staff] and the fact that she didn’t have the discipline of an internal leadership election.

No premier since Alec Douglas-Home has emerged so suddenly and surprisingly; on top of that one of the foremost policies of the entire nation had just been ripped up. In such circumstances it was unsurprising that some mistakes were made, and also that there was quite substantial briefing against the new brooms. I suspect the aforementioned resignation letter will serve as the high-water mark for such briefing!

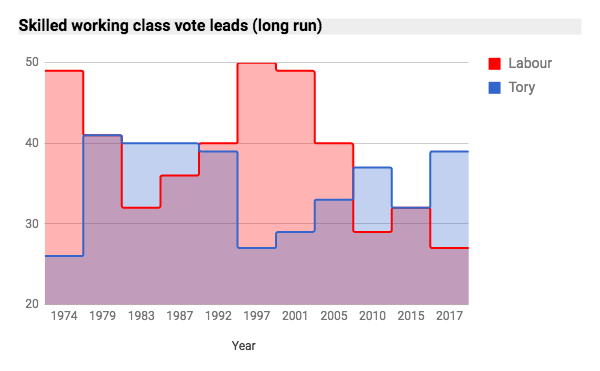

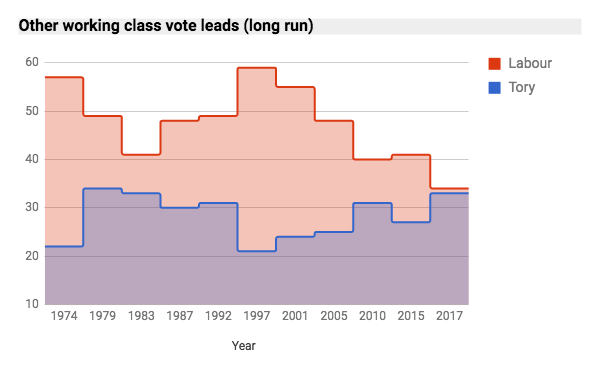

But all the while the Conservatives were pulling further ahead in the polls. Momentum activists may wish to attribute this to the so-called “chicken coup” but, as others on here have noted, the polling was both a reaction to the fact of Brexit and a recognition that Theresa May can reach parts of the electorate that David Cameron simply couldn’t. To borrow a couple of graphs from Theo Bertram:

There are some more figures in his excellent recent blog post, but the core of it is his conclusion that “David Cameron put off working class voters, Theresa May does not.” Allied to the Corbyn effect the top-line polling results are staggering, and Copeland is a clear manifestation of them. Against this, the referendum cleavage still poses substantial risks to the Conservatives, as Alastair Meeks pointed out. The Liberal Democrats are surging against the Tories in council by-elections – in both Remain and Leave areas – and of course they took the Remain heartland of Richmond Park in December. Her strategy may well concede some losses to the Lib Dems at the next general election; the hope is clearly that gains from Labour and the SNP will outweigh them.

It may seem trite but the obvious comparison is indeed with Mrs Thatcher. The Economist article uncharitably describes her first term as shambolic; she certainly struggled with her inherited political position. Monetarism was derided by experts in much the same way that Brexit is. Yet enough people trusted her sense of purpose and the idea that she was fulfilling a mandate for fundamental change. She too broadened the Conservative coalition, aided and abetted by an utterly unsuitable Labour leader.

Brexit remains a unprecedented challenge and the negotiations will bring more certainty, meaning Mrs May may find it difficult to keep all wings of her party satisfied. Like Mrs Thatcher, she will eventually find that no one gets to live forever in politics. But it doesn’t look like she’ll slide away either.