Why is the Tory vote share holding up?

What happened to the unpopularity Cameron predicted?

It’s been an expectation of many pundits and politicians that introducing government cuts will make the government unpopular. Two months ago, David Cameron himself repeated that sentiment. It’s certainly true that for the Lib Dems, government has brought unpopularity but the Tory share has remained just about unchanged. Even the Lib Dems may not be suffering from the cuts in general. The tuition fees issue and trust issue generally has been corrosive and the tactical Labour voters look to have worked out that voting Lib Dems gets you Lib Dem, not Labour, members of parliament.

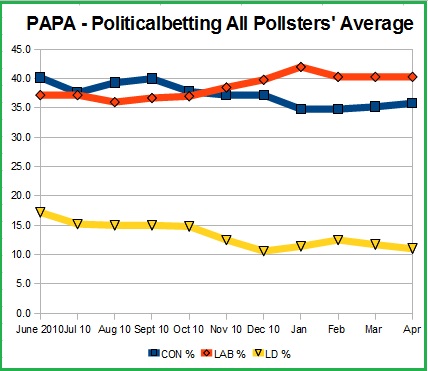

Of the six polling companies to have released surveys in the last two weeks, four (YouGov, ICM, Comres and Populus) have the Conservative vote share at 35 or 36%, almost exactly where it was at the general election a year ago. Mori has it up at 40%, with only Angus Reid down on the year, at 31%.

One thing that has very obviously changed is that Labour are now generally in the lead across most pollsters and politics is of course a relative game: vote share on its own is not all that meaningful a figure. But that the 2010 Conservative voters are sticking with their party is not without significance either. So why’s it happening?

One possible explanation is that as far as Conservatives are concerned, the government’s still in honeymoon territory. This might sound surprising given its approval ratings but those are overall figures. The approval ratings from Conservatives remains very high, and with nearly all 2010 voters in the fold, that approval is of the voters then as well as now.

Looking back at the Mori archive (and recognising the changes in methodology), such extended honeymoons are not uncommon. In both 1980 and 1984, when the government was tackling difficult economic problems, with some or all of high unemployment, high interest rates and spending cuts, the poll share in April was within the margin of error of their winning share the previous year. In 1988 it was actually up, albeit in much more benign circumstances, as it was for Labour in 1998 and 2002. Only in 1993 had the governing party’s vote share slumped. Perhaps this is a case of expectations being framed by the exception rather than the rule.

A second explanation might be that the cuts aren’t hurting yet. Headline figures have been announced and some spending has been earmarked for reductions or scrapping but most of that is still to be implemented: the cuts in 2010/11 were quite modest compared with those scheduled this coming year. Even those that have been implemented won’t hit everyone equally.

A third reason may be that the big argument about the necessity of tackling the deficit has been won, especially with Conservative voters. Even if there is concern or opposition to specific proposals, while Labour continues to appear to oppose every cut and looks ambivalent about sound money, the sort of soft Tory swing voters that Blair attracted in 1997 are unlikely to switch. News stories from Ireland, Portugal and even the United States keep refocusing attention on this critical divide. Indeed, with Labour’s front bench bearing a marked Brownite tendency, the negative reasons that pushed the swing voters who ended up in the blue camp there are likely to still apply.

One suggestion that doesn’t hold good is the contention that even if it is hurting, Conservative voters believe in the smaller-state policies that the cuts programme is inevitably delivering (and other policies besides), and will continue to support it anyway. While it’s true for some, that merely provides for a floor for Tory support, not the retention of near-enough all of it. By no means all last year’s voters were ideologically committed.

I don’t think I’ve been alone in being surprised at the resilience of the Tory numbers. It’s a long time to the next election but working out why the Conservative numbers haven’t plunged may give a good pointer to the battle in 2015.