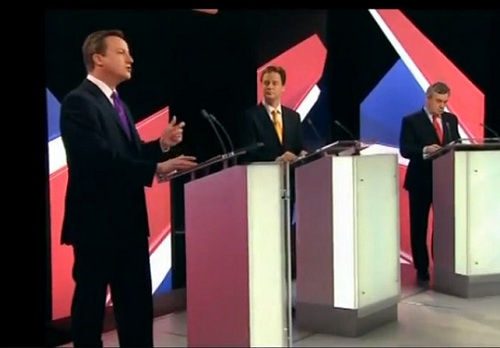

Cameron’s big 2015 debate gamble: to play or to sabotage

The 5-3-2 proposal is unworkable and looks like a wrecking attempt

There’s no doubt that David Cameron looks like someone who wants to avoid the kind of leaders’ debates that dominated the 2010 election. He’s on record as saying that he’d prefer a different format, though the lack of engagement in the process to design them suggests no great urgency on his or his party’s part.

Indeed, the proposal to have three debates – one between him and Ed Miliband, one with those two and Nick Clegg, and one with those three, Nigel Farage and the Green leader (who may change between now and then given their biennial leadership elections) – could have been designed to elicit a rejection from at least one other major party and so throw the onus for a lack of agreement on to whoever rejected it. Except that’s not where the blame would end up; for one thing, it’s too transparent, for another, it runs against the rules on fair coverage and for a third, it wouldn’t preclude a more sensible suggestion being put forward.

While the Lib Dems are still recognised as a ‘major party’ for Westminster elections, it’s not going to be practical to exclude them from any of the debates. Unless Ofcom downgrade their status based on polling and other election results – something highly unlikely given that they were recently granted that status for the Euro-election where historically they do worse than in the generals – the expectation has to be that they’ll be there in all of them.

Similarly, the idea that UKIP should only be granted the same status as the Greens opens up a whole different kettle of fish. The SNP contested the right for the last elections to exist due to their exclusion and while they lost that case, that was partly down to legal tactics and partly because the SNP was clearly a lesser factor in the election across the UK than the three parties that did take part. By contrast, proposing the inclusion of the Greens and UKIP but not other parties with MPs is an open invitation for them to instigate court cases they might well win.

For that matter, while UKIP doesn’t currently have any MPs, it’s tempting fate to base an argument on that when the Newark by-election gives them a reasonable chance of making precisely that breakthrough. Likewise, is it really plausible to place UKIP alongside the Greens if, as polls suggest is eminently possible, Farage leads his party to victory in the European elections?

The scale of that achievement should not be understated: no party other than the Conservatives or Labour has won any national election in over a century. For comparison, the biggest election the Liberals or Lib Dems have won since 1945 is Devon County Council. To class UKIP in the third tier is asking for trouble – which may very well be the plan.

Perhaps the question Cameron (or his team) should be asking is whether he or they are right to be so frightened of UKIP. No doubt they’re still haunted to some extent by the effect Nick Clegg had on the 2010 election campaign after the first debate and are worried that Farage might do something similar. Perhaps he would but it’s far less clear who would be the loser if he did. UKIP speak to socially conservative Labour voters as much as Tory ones.

Either way, putting forward a proposal that Ofcom would likely rule out of order is not going to work, either as PR or on its own merits. The reality is that the media want debates, a goodly portion of the public want debates and some of the leaders will want debates. Standing against them or trying to finesse them off the table will just look bad. He could do a lot worse than just back the same format as last time.