The rise of UKIP: what does it all mean?

By Dr. Rob Ford – University of Manchester

As pb.com readers are doubtless aware, the UK Independence Party had their two best ever by-election results in recent weeks – scoring a record 14% in Corby in mid-November, then topping this again with 21% in the Rotherham by-election last week. This sharp rise in support – and the continued polling and by-election misery of the Liberal Democrats – have understandably lead to a lot of discussion.

-

Where is support for UKIP coming from? What do UKIP leaning voters want? And what are the implications of UKIP’s rise in the polls for British politics going forward?

To answer some of these questions, I can draw on a very large and comprehensive data sources to show this – the British Election Study Continuous Monitoring Survey, conducted by YouGov every month since about 2004. This is an invaluable resource, with detailed information on the views and political preference of hundreds of thousands of voters surveyed over the past 8 years.

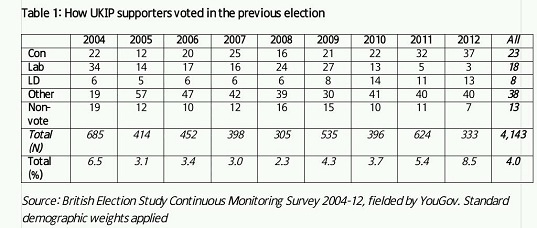

First, let’s take a look at where UKIP voters come from. Table 1 charts how current UKIP voters report having voted in the previous election. Since the Coalition began in 2010, UKIP’s support has more than doubled, from under 4% just after the 2010 election to nearly 9% in the most recent poll months. A big part of this rise is indeed due to Conservative defections – the share of former Conservatives among UKIP voters has risen. But it has risen from a low base. In 2009, roughly 2 in 10 UKIP voters had voted Conservative in the previous election. Now, it is 4 in 10. So, even now less than half of UKIP’s current support is coming from former Tory voters.

Another 40% or so voted “other” in the previous election – these are mostly UKIP loyalists who cast ballots for their current party at the last election. Might such voters be tempted over to the Conservatives? Perhaps, but research I have done with colleagues on UKIP loyalists suggests many come from working class, Labour leaning backgrounds, and are deeply hostile to all the establishment parties. This is borne out in the YouGov data – UKIP supporters’ views of all three parties’ leaders are strongly and persistently negative, and they are more likely to express alienation from politics and dissatisfaction with democracy. It is very doubtful that the Conservatives would sweep such voters if they allied with UKIP. And on top of this, a further quarter of recent UKIP support has come from Labour and the Lib Dems, or from abstainers. These are not groups the Conservatives are likely to win over with an alliance.

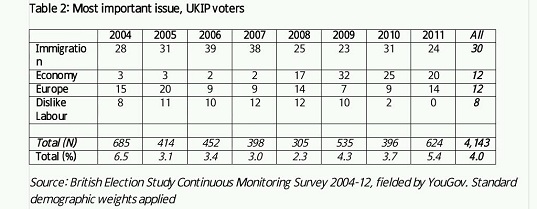

So, while some Conservative support seems to be leaking to UKIP recently, they are by no means solely a home for discontented Tories. This brings us to the second question – what motivates UKIP voters? UKIP politicians themselves tend to trumpet their growing popularity as vindication of their core agenda: Europe. While British voters have become more sceptical about the EU over recent years – unsurprising give the steady flow of “Eurozone crisis” news – there is little evidence that the rise in UKIP support is the result of a surge in concern about the EU.

Table 2 shows the four most popular answers UKIP supporters have given since 2004 when asked what is the most important issue facing Britain. The most popular answer, by far, is immigration, named by 30% of UKIP respondents overall, and the most popular answer in every single year since 2004. Europe has seldom even been the second biggest issue in UKIP voters’ minds: since 2008, the economy has taken precedence, and before that voters were more likely to point to a general dislike of the Labour government. To put in bluntly, most UKIP voters (unlike most UKIP politicians) do not regard Europe as the main issue on the agenda.

So UKIP’s rise is clearly not the result of temporary defections by Conservative voters annoyed about Europe. What, then, is going on? My ongoing research with Matthew Goodwin suggests that UKIP shares many characteristics with “radical right” parties such as the Dutch Party for Freedom, the Danish People’s Party, the Austrian Freedom Party and the True Finns. Like these parties, UKIP mobilises voters who are primarily concerned about immigration, but are also typically nationalist, Eurosceptic and deeply disaffected with the existing political elite. In many cases these parties, or their leaders, began on the mainstream right, before breaking away to focus on a more populist agenda.

UKIP’s evolution has been similar – it began as a rebellion on the centre-right over Europe, but under Nigel Farage has developed a broader populist and anti-immigration agenda. UKIP’s appeal – anger over immigration, anxiety about national identity, hostility to the EU and a deep disaffection with “politics as usual” – cuts right across traditional party dividing lines, enabling the party to recruit angry voters regardless of who is in charge. As table 1 shows, UKIP was as successful winning over grumpy Labour voters during the previous government as it is at winning grumpy Tories now.

What lessons can the parties draw from all this? The Conservatives need to realise that Michael Fabricant’s plan for a blue-purple alliance is, in the words of one of my colleagues, “the politics of not understanding data”. UKIP voters are a more diverse, and disaffected, lot than right wing Conservative backbenchers seem to realise. Most are not former Conservative voters, and are unlikely to be thrilled if their party – which recently ran on the slogan “Sod The Lot: vote UKIP” – were to align itself with a political elite which disgusts them. A UKIP alliance will deliver few votes, and less seats. Indeed, by alienating moderate voters, such an alliance could do more harm than good.

Labour should not celebrate the rise of UKIP either. UKIP’s agenda – hostility to immigration, social conservatism, Euroscepticism and populism – proved almost as appealing to Labour voters in 2004-10 as it is to Conservatives right now. UKIP’s strongest support often comes from older working class voters, who often have traditional left wing loyalties. A strong UKIP will pose as many problems for an incoming Labour government as it does for the Conservative incumbents.

Finally, UKIP politicians and activists themselves need to develop a clearer understanding of what the surge in UKIP support means. UKIP’s voters, new and old, are angry about immigration, threatened by social change, and deeply hostile to the political class. This does reflect a coherent set of public concerns – we find it in other countries too – but it is not the concerns which most exercise many UKIP activists, who are often focussed on deregulation, tax cuts, and above all, Brussels.

This disconnect raises a serious problem for UKIP: it cannot become a genuine “third force” in British politics without an activist base able to mobilise voters. Yet the concerns which seem to attract activists to UKIP are very different to those which attract voters to the party. This may explain why UKIP’s persistent inability to break through in local elections – the party lacks the candidates and activists willing to undertake the hard slog of local politics, or a coherent agenda to sell to local voters.

This is the difference between the Liberal Democrats and UKIP. The Lib Dems have a relentless focus on local organisation, and use this to channel popular discontent into local election wins, by-election wins, and eventual Westminster success. Tip O’Neill once observed that “all politics is local”, and under first past the post this is the brutal truth: UKIP may carry on rising in the national polls, but without local strongholds they will win nothing in a general election. Nigel Farage is riding high right now, but without a radical shift in party strategy I wouldn’t bet on seeing him or any of his colleagues warming the benches of the House of Commons in 2015.

Doctor Rob Ford is a Politics Lecturer at the University of Manchester. He’s currently working on a book with Matthew Goodwin which looks at support for the BNP and UKIP. Due out in about a year.